Newton St Cyres History Group

|

Newton St Cyres History group meet monthly from September to May usually in the club room of the village hall, on a Wednesday evening between 7.30 and 9pm. In the summer we have an outing usually involving a meal or a cream tea. We try to choose speakers on as local topics/issues as possible. We are sometimes fortunate to have members speak on their own local research. Every two years we stage an exhibition for the Newton St Cyres Revels. We do not have a formal membership, everyone is welcome for an entrance fee of £2 to include tea and biscuits. For further information contact [email protected]. |

|

New in the the History Group section

1. Details of the History Group Publications

2. The Tithe map of 1843 has been split up into usable pieces providing fascinating insights into the life of the

whole parish over 175 years ago

3. All the available census data for the parish from 1841 onwards is now available. You can see who lived in your

house or trace your village ancestors

4. From Church records there are the Births Marriages and Deaths recorded in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

2. The Tithe map of 1843 has been split up into usable pieces providing fascinating insights into the life of the

whole parish over 175 years ago

3. All the available census data for the parish from 1841 onwards is now available. You can see who lived in your

house or trace your village ancestors

4. From Church records there are the Births Marriages and Deaths recorded in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

History Group Publications

From time to time, the Newton St Cyres History Group sponsors the research and publication of pamphlets and historical data by interested local historians. Extracts of each are viewable below. Copies of the full documents can be obtained at History Group events or by contacting Jean Wilkins (851337)

|

Newton St Cyres Mining and Miners

Our mining heritage, both manganese, claimed to be “the first commercially successful manganese mines in the world!”, and lead & silver up on Tin Pit Hill that may go back to Roman times. |

NStC Historical Village Walks

four brief walks around the village –“The Parish Hall, formerly a cider house” and many others |

Memories of Boyhood in a Devon Village

Written by Alfred Abraham, born in Newton St Cyres in 1893. He shares his memories growing up in the village at the beginning of the 20th century |

|

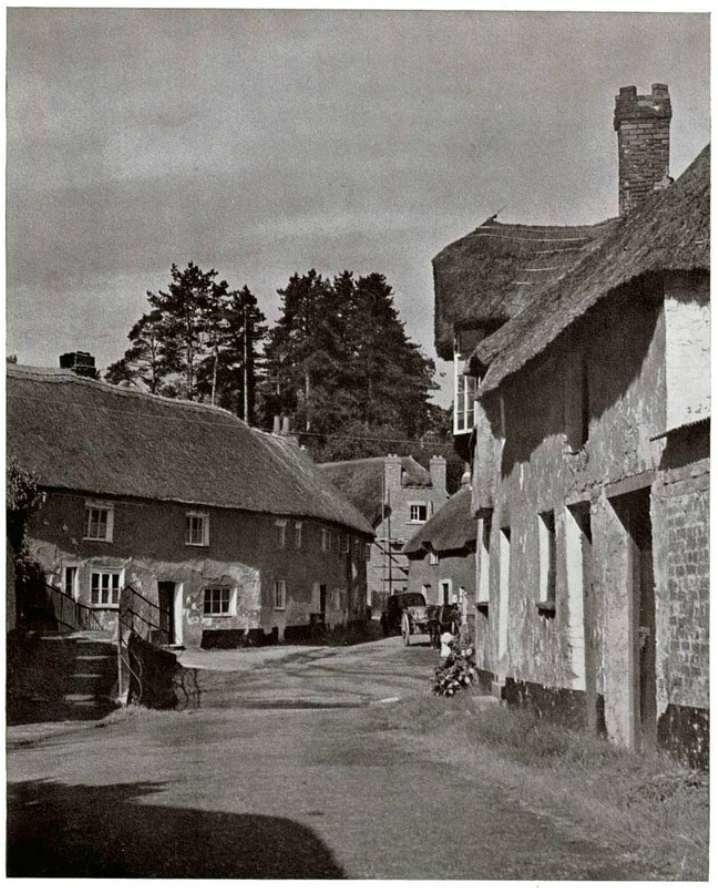

Newton St Cyres – A Village Story Compiled by residents of this village in 1999 (the green ‘millennium book’) containing a wealth of reproduced photographs. Newton St Cyres Church – Statement of Significance Describes the history and most important features of the church, dedicated to St Cyr and St Julitta. |

Newton St Cyres in the 1940s & 1950s Written by Stella Cork, born in Newton St Cyres in 1934 and the daughter of the village postmaster. She gives a remarkable description of families in the village and an insight into village life. |

Newton St Cyres and The Civil War 1642-46 The story of grief, hardship and a little excitement for those living in the village almost 400 years ago during the English Civil War supported by coloured photos and maps. Would you have been a Roundhead or a Cavalier? |

Births Deaths and Marriages in Newton St Cyres

1555 - 1799

1555 - 1799

Parish Registers have been largely kept for all baptisms, weddings and funerals in the UK since 1555. With the support of the History Group, These have been transcribed and consolidated for all births, marriages and deaths (BDMs) for the 16th, 17th and 18th century that were registered in Newton St Cyres Church.

We have also sorted the information alphabetically so that for each century you can see all the entries for a particular surname (spellings are not always consistent!). There are many families who have been parishioners in Newton St Cyres throughout this period and in some cases descendants still live in or near to the parish.

UK Censuses of Newton St Cyres

A UK census typically takes place every decade. Public access is normally restricted under the terms of the 100-year rule. With the support of the History Group, we have transcribed and consolidated all the records for Newton St Cyres between 1841 and 1911.

These give a very vivid picture of the family members of each household. In many cases the property is identified whereas in others you may just have to imagine yourself walking up and down the village lanes as the census taker would have to interview each household.

These give a very vivid picture of the family members of each household. In many cases the property is identified whereas in others you may just have to imagine yourself walking up and down the village lanes as the census taker would have to interview each household.

Newton St Cyres Tithe Map of 1843

Tithe maps applied to English parishes and were prepared following the Tithe commutation Act 1836. This act allowed tithes to be paid in cash rather than goods. The map and accompanying schedule gave the name of all owners and occupiers of land in the parish.

With the support of the History Group, analysis has been done to cross-reference each building reference in the tithe schedule with its location on the map. These 18 images shows the detail of our village and surrounding villages and farms and homesteads. It is remarkable how so much of detail from over 175 years ago remains intact today.

(Click on Map below)

Report 6 Exeter City Wall Redcoat Tour March 2011

Report 8 Victorian Crediton History John Heal May 2011

Report 9 DevonHedges Cressida Whitton June 2011

Report 18 The history of the Devon Longhouse Tom Coleman May 2012

Report 30 Artifacts found with metal detector Colin Hart May 2013

Report 43 East Holme Farm newton St Cyres Peter Kay December 2014

Report 44 Monmouth's Rebellion Roger Mortime February 2015

Report 45 Christmas, Readings and Reports Christopher Lee, Ian Maxted and Judi Binks February 2015

Report 46 Westcountry and Dartmoor Buildings Paul Rendell March 2015

Reports from Meetings 2018

Wed. January 17th 2018

It was a wet January evening for our first meeting of 2018, but we had a good audience to watch a series of farming films, presented by Mike Brett. Mike Brett, with his wife, Rebecca, has been a welcome presence at most of our meetings in recent years, as he is a skilled film maker and records the meetings as part of his involvement with the Sandford Heritage Group. We thus have a useful record of many of our speakers. Sandford Heritage Group have done a lot of work on the farms in the parish, and in conjunction with this, Mike has filmed local traditional agricultural events. He has also had access to a rare set of home movies inherited by Karen Stephens of Swannaton Farm, which he has edited. These date from the 1930s and 1940s, may be into the 50s as well, though the dates have to be estimated from looking at the clothes and the cars as the exact dates are unknown.

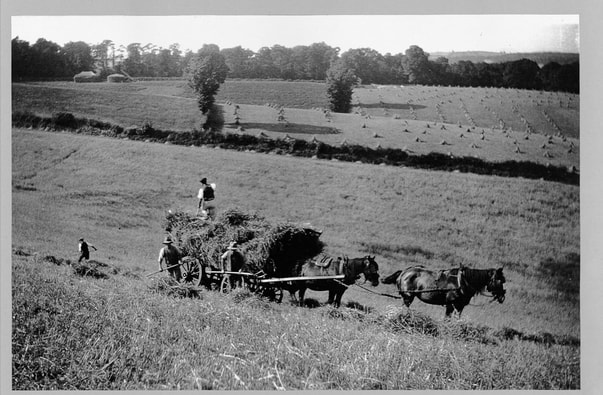

Our evening began with watching this 20+ minute black and white film, which was completely fascinating. The first sequences showed hay making, using a very tall hay pole, supported by ropes, with a swinging metal grab which lifted the bundles of hay into place. Horses both powered the lifting and helped gather the hay up into heaps, but this last job was also being done by a car fitted with a buck rake at the front, driven around the field by a young woman. One endearing shot showed her refilling the car with water and smiling at the camera, and another with the car full of children. The rick was basically square, and we watched it grow higher and higher, and in a later shot we could see it or a similar one, safely thatched and finished. Another hay making process was shown as the hay was pitchforked high onto a traditional high ended wooden waggon, and then moved to a barn and transferred to its shelter.

A reaper-binder machine drawn by three horses came next, moving accurately around the field, whilst women and children stacked the sheaves. Mike said that in the Sandford area the sheaves are stacked into ‘stitches’, but everyone in the clubroom used the word ‘stooks’ instead. A ‘stitch’ must be a very local dialect word. The film went on with lots of footage of cattle, mostly dark coloured and horned, sheep and sheepdog, and flocks of fowl being fed and then plucked for sale. The farm buildings and houses were clear but not recognised by anyone as yet – it would be good, Mike commented, to identify them. From the surrounding countryside, hilly and stone-walled, it is assumed to be near Tavistock where Karen Stephens' family come from. The family members were also recognisable and included scenes of a large picnic, cider drinking, horse riding, mother and toddlers, and more children playing or with the farm animals and their dog. A lovely shot was of a big pig wandering in front of a pair of toddlers in their romper suits, feeding the hens, and then the same or another sow with a large litter of piglets.

|

It was clear from the films how much more manpower (and woman and children power) was needed to run a general farm, compared to the more focussed and mechanised systems used now. From this, another picture emerged of the sense of purpose people must have gained from working together to get the various tasks done.

Next, Mike offered us the choice of 4 shorter films which he had taken at local events, which were steam ploughing, cider pressing, heavy horses and thatching reed cutting. We watched them all! First off was the steam ploughing, requested by Christopher Southcott, as he remembered seeing a traction engine used to clear a silted up turnip washing pond at Clannaborough, about fifty years ago. This film showed how two large steam engines were used for ploughing, one at either end of the field, at an event at Ashreigny in September 2011. A steel cable spanned the field and the plough was hauled up and down, steered by one |

Threshing Churchyard Down 1942

|

man with two others for ballast! This had been a vintage tractor day also, and so there were lots of shots of old tractors, still in working order, and reminding us how radically they changed farming methods and how labour saving they were and are.

The cider pressing film (not shot by Mike) was made at Prowse Farm in 2015. Peter Stoyle and his son were demonstrating how the apples were crushed and then the press filled with alternating layers of long straw reed, straw and apple pulp. The sides were skilfully folded in so that the juice could not escape, and then when the high beehive-like structure was complete, the press was wound down and the juice poured out, to be tapped off into containers ready for fermenting.

The film of cutting wheat for thatching was taken at Henstill Farm, Sandford. Keith White has a great interest in old farm machinery and grows a large field of long straw for thatching use, and harvests it traditionally. We saw the binder reaper cutting the wheat and making sheaves, which was then put into ‘stitches’. A clear striation in colour showed that the crop was ready to be harvested. Then a 1910 comber removed the chaff and grain, and prepared the straw into bundles

The film of cutting wheat for thatching was taken at Henstill Farm, Sandford. Keith White has a great interest in old farm machinery and grows a large field of long straw for thatching use, and harvests it traditionally. We saw the binder reaper cutting the wheat and making sheaves, which was then put into ‘stitches’. A clear striation in colour showed that the crop was ready to be harvested. Then a 1910 comber removed the chaff and grain, and prepared the straw into bundles

ready for thatching, the waste straw being made into bales by a traditional baler. This large machine required several men to feed it with the sheaves, and keep the rhythm of work going as the thatching bundle, grain and chaff and bales were produced. It was hypnotic to watch. Mr White is helped by his grandchildren, and mike pointed out that although a tractor now powers the process, originally the belts would have been linked to a traction steam engine.

The final film was of the heavy horse ploughing at Netherexe in 2011. The animals were beautifully paired and groomed, and adorned with splendid harnesses. They were mostly pulling ploughs although there was a pair pulling a wagon to give people rides. It was most interesting, though, to see three black horses pulling a reaper just like the one we had watched on the black and white film made in the 1940s, 70 years earlier. The job is clearly very skilled, as the operator has to control the horses, around right angled corners, and also steer and operate the machine and its processes.

This was a satisfying note on which to end, and our thanks go to Mike Brett for his time and expertise, and a most interesting evening.

Meetings will be held on a WEDNESDAY evening

7.30pm in the Village Hall Club Room.

We have no special membership and everyone is welcome.

There is a small charge of £2 which includes tea and biscuits.

For further information contact Jean 851337 Isobel 851351

The final film was of the heavy horse ploughing at Netherexe in 2011. The animals were beautifully paired and groomed, and adorned with splendid harnesses. They were mostly pulling ploughs although there was a pair pulling a wagon to give people rides. It was most interesting, though, to see three black horses pulling a reaper just like the one we had watched on the black and white film made in the 1940s, 70 years earlier. The job is clearly very skilled, as the operator has to control the horses, around right angled corners, and also steer and operate the machine and its processes.

This was a satisfying note on which to end, and our thanks go to Mike Brett for his time and expertise, and a most interesting evening.

Meetings will be held on a WEDNESDAY evening

7.30pm in the Village Hall Club Room.

We have no special membership and everyone is welcome.

There is a small charge of £2 which includes tea and biscuits.

For further information contact Jean 851337 Isobel 851351

Reports from Meetings 2017

December 13th 2017

Our 2017 Christmas Meeting was on Wednesday 13th December. The committee had organised seasonal refreshments instead of our usual tea and biscuits, and the club room was cheerfully decorated. The evening was split into two sections. First Christopher Southcott showed us aerial films of the village, and then Roger Wilkins read an atmospheric ghost story. Christopher Lee had kindly agreed to do a reading but was called away to help his aunt on Exmoor, and so Roger stepped in.

Brian Please acted as Master of Ceremonies, and introduced Christopher by explaining that the films had been made using a drone, belonging to his son. Brian pointed out that none of us would have seen from the air all the usual sights that we walk and drive past regularly, so now was our chance! It was fascinating to see the films. The first one started off looking down on the Beer Engine, the Recreation Ground and the Railway Station, and then followed the road over the site of the Long Bridge, which used to be between the present bridge and the Railway Bridge. It spanned a leat which may have taken water from the river to a mill, and there also used to be a row of cottages there. When the Creedy floods badly, it is clear to see from the flow of water where this channel used to be, although it is long since silted up and disused. The Longbridge Cottages were demolished in 1906.

The film then moved along to the present river bridge, which dates from the sixteenth century. Christopher explained that the coping stones were originally wooden, and that there is a record from 1734 of a cost of £8 to repair the bridge. The road was widened in 1831, and the flood culvert built when the road was raised in 1939, because the flooding was regularly

so bad as to make the road impassable. The County Boundary stone, marked CB and visible in the wall on the village side of the bridge, marks the line up to which the Parish was responsible for the road maintenance. After that the County was responsible because the bridge was a major structure.

After this Christopher showed some video films of recent bad floods from 1999 and 2000, made by himself and Peter Watts. They showed the road flooded and the fields and football pitch covered with water, and reminded us how much flooding can still happen, and how much erosion the water can cause.

After this we all enjoyed refreshments and conversation, whilst Christopher showed more drone footage of the Church, Newton House, Home Farm, and the main part of the village. It was informative to see how things look familiar and yet very different from the air, and how they link together in a new way.

We then resumed out seats, lowered the lights, and lit a lantern to listen to Roger’s Christmas ‘ghost’ story from 1896. It was set in a Devonshire town at the Cat and Fiddle pub at the coming of age celebrations of the son of Squire Thornley. Two men were seeking the hand of the young lady helping at the bar, but after the taking of much liquid refreshment, and the singing of Widdecombe Fair, with its ghostly ending, Constable Davey, one of the suitors, was terrified by a ghostly hand and strange groans emerging from a grave in the churchyard. Of course, the village reprobate had fallen in to a newly dug grave and was trying to get out, but the Constable’s reaction lost him the favour of the girl for it was her father!

This ended the proceedings but left time for more refreshments and discussion before everyone said their goodbyes. Our thanks go to Christopher for showing the video films, and to Roger, for stepping in to entertain us.

7.30pm in the Village Hall Club Room.

We have no special membership and everyone is welcome.

There is a small charge of £2 which includes tea and biscuits.

For further information contact Jean 851337 Isobel 851351

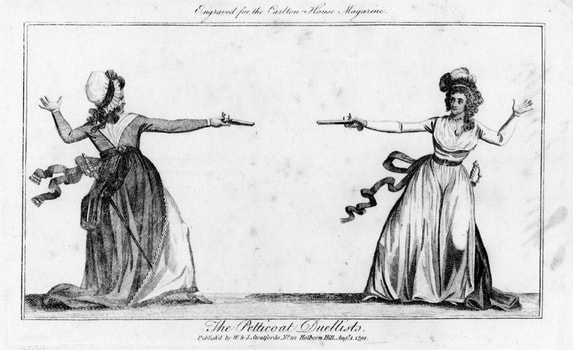

DUELS SINCE 1760

For our November meeting we welcomed David Pugsley, an expert in law, to tell us about the practice of duelling which he did with many interesting examples. Ably assisted by Claire and Clive Rendle, dressed as two ladies of the late eighteenth century nobility, Clive fetchingly ‘made up’ and bewigged (he acted the part of the elder lady), David introduced us to the Petticoat Duel. The two ‘ladies’ were having tea together when the conversation mentioned the age of the elder who was trying to pass as much younger. An argument ensued and the elder regarding her honour breeched, challenged the younger to a duel with both swords and pistols. The props were real and the pistols were very heavy. Both ladies retired unharmed. This duel was later admitted to be a spoof. Ladies did not duel in England but they did so, on the Continent.

Duelling had grown out of the medieval laws of chivalry and was very much about a gentleman protecting his honour. To address a gentleman as a scoundrel or rascal was a slur upon his honour.

In 1792 in Mount Street, Mayfair, a row of houses of the nobility with many servants, they had been celebrating the King’s Birthday. However celebrations turned to riots, windows were broken and carriages were scratched. Thus it was that the guards moved in and so when Lord Lonsdale arrived in his emblemed carriage, Captain Cuthbert not only attempted to prevent his annoyed Lordship’s entry to the street but also called him a ‘rascal’ for defying the Law. His Lordship considered this an assault on his honour, so Cuthbert was challenged to a duel. The duel took place at daybreak with pistols and both missed with the first shot. With the second shot Lonsdale’s bullet was stopped by a button on Cuthbert’s coat. His Lordship considered his honour restored and they shook hands and went home.

The accepted code of duel conduct varied between countries. In England pistols or swords could be used until 1784. Thereafter only pistols were used. The number of paces apart was generally 10 or 12 but the exact rules for any single duel were decided by the seconds, generally friends of the contestants. A site out of town was usually chosen, and 6am the time, before there were public onlookers. The starting signal varied, it could be a countdown or the dropping of a white handkerchief. Often the seconds would try to conciliate to prevent the duel and may at times have agreed between themselves not to load the pistols ( a duty they must perform together) or supply enough powder.

Sometimes it would be agreed that one contestant fired first. He might take care to miss and then trust his opponent would fire in the air. Both could then return home honour satisfied. However there were deaths. The English legal system of the time did not allow those prosecuted to give evidence. As the murderer could not give evidence, or the seconds, as they were prosecuted for aiding and abetting, it often happened that a case could not be proved. David gave the example of a Welsh duel where the agreement was that the parties should start back to back, walk 10 paces, and then turn and fire. However one took only 5 paces, and turned and shot his opponent in the back. Since there were no witnesses apart from the surviving principal and the two seconds, who could not give evidence on oath, the verdict of the Coroner’s jury was wilful murder, against some person or persons unknown!

In England duelling could be considered a game of sport for gentlemen. They would normally finish by shaking hands. If the police intervened they would be bound over by the Magistrates to keep the peace. In 1798 a sum of two thousand pounds was demanded from the contestants as surety. In the reign of George 3rd (1760-1820) the Times reported 172 duels and 69 deaths. 96 were wounded and 179 unhurt. There were 18 trials, 3 verdicts of murder and 2 persons hanged, both of whom were Irish, where duelling was taken very seriously. The first conviction for murder was in Exeter in 1799 before Mr Justice Buller when a free pardon was given. George 3rd’s sons were keen duellers and many free pardons were given.

For our November meeting we welcomed David Pugsley, an expert in law, to tell us about the practice of duelling which he did with many interesting examples. Ably assisted by Claire and Clive Rendle, dressed as two ladies of the late eighteenth century nobility, Clive fetchingly ‘made up’ and bewigged (he acted the part of the elder lady), David introduced us to the Petticoat Duel. The two ‘ladies’ were having tea together when the conversation mentioned the age of the elder who was trying to pass as much younger. An argument ensued and the elder regarding her honour breeched, challenged the younger to a duel with both swords and pistols. The props were real and the pistols were very heavy. Both ladies retired unharmed. This duel was later admitted to be a spoof. Ladies did not duel in England but they did so, on the Continent.

Duelling had grown out of the medieval laws of chivalry and was very much about a gentleman protecting his honour. To address a gentleman as a scoundrel or rascal was a slur upon his honour.

In 1792 in Mount Street, Mayfair, a row of houses of the nobility with many servants, they had been celebrating the King’s Birthday. However celebrations turned to riots, windows were broken and carriages were scratched. Thus it was that the guards moved in and so when Lord Lonsdale arrived in his emblemed carriage, Captain Cuthbert not only attempted to prevent his annoyed Lordship’s entry to the street but also called him a ‘rascal’ for defying the Law. His Lordship considered this an assault on his honour, so Cuthbert was challenged to a duel. The duel took place at daybreak with pistols and both missed with the first shot. With the second shot Lonsdale’s bullet was stopped by a button on Cuthbert’s coat. His Lordship considered his honour restored and they shook hands and went home.

The accepted code of duel conduct varied between countries. In England pistols or swords could be used until 1784. Thereafter only pistols were used. The number of paces apart was generally 10 or 12 but the exact rules for any single duel were decided by the seconds, generally friends of the contestants. A site out of town was usually chosen, and 6am the time, before there were public onlookers. The starting signal varied, it could be a countdown or the dropping of a white handkerchief. Often the seconds would try to conciliate to prevent the duel and may at times have agreed between themselves not to load the pistols ( a duty they must perform together) or supply enough powder.

Sometimes it would be agreed that one contestant fired first. He might take care to miss and then trust his opponent would fire in the air. Both could then return home honour satisfied. However there were deaths. The English legal system of the time did not allow those prosecuted to give evidence. As the murderer could not give evidence, or the seconds, as they were prosecuted for aiding and abetting, it often happened that a case could not be proved. David gave the example of a Welsh duel where the agreement was that the parties should start back to back, walk 10 paces, and then turn and fire. However one took only 5 paces, and turned and shot his opponent in the back. Since there were no witnesses apart from the surviving principal and the two seconds, who could not give evidence on oath, the verdict of the Coroner’s jury was wilful murder, against some person or persons unknown!

In England duelling could be considered a game of sport for gentlemen. They would normally finish by shaking hands. If the police intervened they would be bound over by the Magistrates to keep the peace. In 1798 a sum of two thousand pounds was demanded from the contestants as surety. In the reign of George 3rd (1760-1820) the Times reported 172 duels and 69 deaths. 96 were wounded and 179 unhurt. There were 18 trials, 3 verdicts of murder and 2 persons hanged, both of whom were Irish, where duelling was taken very seriously. The first conviction for murder was in Exeter in 1799 before Mr Justice Buller when a free pardon was given. George 3rd’s sons were keen duellers and many free pardons were given.

|

The duellist’s stance was important, and he would stand sideways and keep his elbow bent (Kilkenny style) to protect his chest and abdomen. It became the practice to take along a surgeon ready to treat the wounded. However he could be prosecuted for aiding and abetting the murder. In 1803 there was a case of two people riding in Hyde Park with their dogs when one dog attacked the other. One rider hit the attacking dog and was challenged to a duel. He took the King’s Surgeon with him. The surgeon was tried at the Old Bailey but was acquitted. Not surprisingly, surgeons were reluctant to attend duels but, as in the case on Haldon in 1833, often “happened to have been passing by” on the way to attend a patient!

It was a misdemeanour to challenge for a duel and the challenged party could appeal to a Magistrate, as did Edward Divett MP when challenged by an Exmouth man. Before rules were introduced by Erskine May for behaviour in Parliament in the 1840’s insults in the House of Commons were frequent. The Foreign Secretary and the Minister for War, Castlereagh and Canning fought in 1813. Canning was injured in the thigh, but the wound was not serious. |

In 1829 the Duke of Wellington was appointed as Prime Minister on a promise not to bring Catholics into public life. He did and was challenged by Lord Winchelsea. The Duke fired first and missed and Winchelsea fired in the air and apologised.

In the 1852 General Election there was name calling. Perfidy applied to one gentleman provoked a duel. The parties took a train to Weybridge, walked over two fields and still found spectators, so they took a carriage together and found a quiet place only to be disturbed by a cock pheasant taking off noisily. They gave up and rushed home only to see a little later a letter in the Times from the Cock Pheasant pointing out it was not the beginning of the shooting season yet! This was the last recorded duel in England and was the English ‘laughing it out of court’.

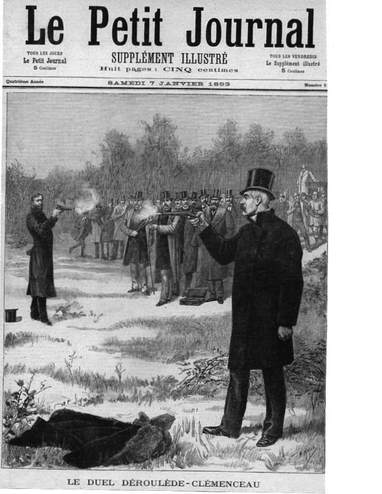

The French and the Germans took duelling more seriously and it continued in those countries much later. The French had no rules of behaviour in their National Assembly so insults were sometimes settled by duels. In 1892 Clemenceau, the future Prime Minister, was accused of corruption by Deroulede, and a duel was fought outside Paris at 25 yards with pistols. There were three shots, but all missed. In England they would have shaken hands. Deroulede refused. The last duel in France was in 1967 when Gaston Defferre, then Minister of the Interior, said to Ribiere: “Tais-toi, abruti,” (Shut up, numbskull). This duel was with rapiers, and Defferre won when he drew blood twice. It can be watched on U Tube.

The Germans were very keen on duelling into the First World War years, undergraduates and young army officers being mainly involved. In 1913 16 young army officers were killed duelling. The practice had died out by 1918.

Russians too were keen duellers, and this was how, in 1837, the poet Pushkin met his death. He had already survived many duels when he challenged a Dutchman, who he believed had interfered with his wife. It was winter and the seconds had to flatten three feet of snow. Ten yards was the agreed distance, they went another five yards away, had one bullet each and then walked towards each other ready to fire. The Dutchman hit Pushkin in the bowel, he dropped his pistol, but they gave him another. His shot hit the Dutchman’s buttons and he got up. Pushkin died in agony 48 hours later. It was suspected the Dutchman was wearing a bullet proof jacket.

These were just some of the examples given. David has quite a repertoire of them. His talk was followed by many questions which showed the appreciation of his audience.

Jean Wilkins

In the 1852 General Election there was name calling. Perfidy applied to one gentleman provoked a duel. The parties took a train to Weybridge, walked over two fields and still found spectators, so they took a carriage together and found a quiet place only to be disturbed by a cock pheasant taking off noisily. They gave up and rushed home only to see a little later a letter in the Times from the Cock Pheasant pointing out it was not the beginning of the shooting season yet! This was the last recorded duel in England and was the English ‘laughing it out of court’.

The French and the Germans took duelling more seriously and it continued in those countries much later. The French had no rules of behaviour in their National Assembly so insults were sometimes settled by duels. In 1892 Clemenceau, the future Prime Minister, was accused of corruption by Deroulede, and a duel was fought outside Paris at 25 yards with pistols. There were three shots, but all missed. In England they would have shaken hands. Deroulede refused. The last duel in France was in 1967 when Gaston Defferre, then Minister of the Interior, said to Ribiere: “Tais-toi, abruti,” (Shut up, numbskull). This duel was with rapiers, and Defferre won when he drew blood twice. It can be watched on U Tube.

The Germans were very keen on duelling into the First World War years, undergraduates and young army officers being mainly involved. In 1913 16 young army officers were killed duelling. The practice had died out by 1918.

Russians too were keen duellers, and this was how, in 1837, the poet Pushkin met his death. He had already survived many duels when he challenged a Dutchman, who he believed had interfered with his wife. It was winter and the seconds had to flatten three feet of snow. Ten yards was the agreed distance, they went another five yards away, had one bullet each and then walked towards each other ready to fire. The Dutchman hit Pushkin in the bowel, he dropped his pistol, but they gave him another. His shot hit the Dutchman’s buttons and he got up. Pushkin died in agony 48 hours later. It was suspected the Dutchman was wearing a bullet proof jacket.

These were just some of the examples given. David has quite a repertoire of them. His talk was followed by many questions which showed the appreciation of his audience.

Jean Wilkins

October 18th 2017

Our meeting in October featured Family History, with its links to archaeology and DNA, and was a skilfully integrated talk explaining all the steps and avenues of family research illustrated by the unfolding and increasingly addictive family research of the speaker, Dr Peter Marsden.

Many of us uncover basic documentary evidence of our family histories but few of us use all the available resources to give as big a picture of past lives as is possible. Peter, as a retired archaeologist, has professional knowledge and he was able to show us how links can be made with archaeology by visiting the areas where ancestors lived and how DNA technology can give insights into family origins and at times come into conflict with existing ideas.

Peter was lucky and inherited a Marsden family tree from a Great Great Grandfather and also written ‘memories’ from a 3x Great Grandfather. Most of us have old photographs and have or had access to oral history. Birth, marriage and death certificates are available from 1837 although expensive. Census records are invaluable and for some places available from 1831. From 1851 they are more informative. Gravestones, wills and obituaries may be found, and house deeds can yield useful information and may be lodged with the Record Office or with the present owner.

Census material revealed that the Marsden family moved from the village of Paythorne (NE of Clitheroe) to the Lancashire mill town of Nelson during the 1850s. Nelson was originally called Marsden but as there was also a Yorkshire town by that name the coming of the railway necessitated a change and the Lancashire town was called after a local pub!

A visit to Nelson and a study of old maps revealed a Marsden Street near the centre of town. Peter’s Greatx3 Grandfather was a mason and had built the houses there, two up, two down cottages. Census material showed how these were often occupied by large families and by looking at the neighbours it was possible to build up an idea of the community there in a newly expanding cotton town. Photographs were obtained from a local newspaper just before 20th century demolition and included plans of the house layouts. The carved stone street sign is now in the local museum.

Architectural and Historical Evaluations may be commissioned from professionals, for old houses. Peter gave two examples: the first was Combe Hayes Farm house near Honiton, former home of his wife’s family. After sale the house was gentrified and such a report produced. The second was one he had done himself on a former home in Hastings. All the rooms are carefully inspected and measured, plans drawn up, and old features described. The house history is followed, using the Tithe map as a key start in this. An excavation in the back garden of the house in Hastings revealed clay pipes and an amazing array of crockery, some of it from Normandy. Bones gave an idea of the diet of the occupants.

Eastholme in Newton St Cyres has had a similar survey and Peter Kay has shared that information with our group.

We were then given hints on reconstructing the communities of our ancestors. In Peter’s case this was to look at how Nelson grew and came of age. In 1851 Thomas Marsden was born in Paythorne in Gisburn. By 1854 Marsdens were building houses in Nelson. Using census material he constructed a graph to show the exodus of families from Paythorne and compared this with a similar graph to show the increase in population of Nelson a town of developing cotton mills. Overcrowding was rife and a 3x Great grandmother Marsden died as a result of contaminated well water. The Marsden family saw needs as opportunities and set up the Marsden Building Society. They set up the water company and were active on the committee for the laying of sewers.

Peter then proceeded to follow his family back into the 18th century giving us a warning to beware the Gregorian, Julian calendar change. He used the Gisburn Parish Registers to follow his Paythorne relatives. According to his inherited family tree Peter had an ancestor who was MP for Clitheroe and lived at Wennington Hall. However he found his line to go back to John Marsden, illegitimate son of Mary Danser who had a further three illegitimate children, and was so poor that she was excused the Hearth Tax. This is where DNA results were interesting. Peter had his done to a high level of sophistication and was informed that a man named Morley had an amazingly close match with his Y chromosome. A visit to Wennington Hall revealed that at the time of John Marsden’s birth (1667) it was occupied by Henry Morley! So, did Henry Morley pay Thomas Marsden to assume parentage of John? A further twist in the story is that Wennington Hall was sold to a Henry Marsden in 1673. Disputed property rights still exist for a nearby building and the old papers are withheld by the current owner. Maybe these will complete the story?

Paythorne, home of Mary Danser and of successive generations of Marsdens, is a small village and some of the old cottages have survived, giving an idea of the sort of home she may have had. Using the Tithe map of circa 1840 Peter found field number 22 was labelled Marsden Croft, and surmised that is where his family farmed in the 18th century. Now it is rough pasture but aerial maps revealed the site of a cottage and its kitchen garden, another small building and two enclosures. Aerial maps with snow cover showed the ridges and furrows of pre-enclosure open fields. Further information can be obtained from local village papers such as Churchwarden’s accounts. Paythorne is a deserted Medieval village.

Family names and DNA was the next topic, names may relate to places, occupations, patronyms, or personal characteristics. We cannot assume that people of the same name are related.

The male Y chromosome is important and is constant from father to son apart from small mutations over periods of time. It gives us a means of indicating which wave of migration we may identify with. Most men in the UK have a Y chromosome R1B showing there was colonisation of Britain after the Ice Age from the Iberian Peninsula. Most women have H1 type mitochondrial DNA which originated in the Basque country. These were the DNA types of the round house inhabitants of Dartmoor.

Peter revealed that he has a Y chromosome that is R1A. Only 5% of British men have this and it has a Scandinavian origin. Thus he wondered if he was descended from fearsome Viking rampagers and pillagers! He has Northern family roots in an area with Viking names and the village of Marsden from which his family take their name would have been on the route from York to Preston, two well known Viking strongholds. Dublin was also a Viking stronghold from which they were later expelled and many would have settled across this same country.

This was an amazing evening and we were held spellbound for more than an hour. We thank Peter very much for letting us follow the fortunes of his family and in so doing learn more about how to enhance our own family histories.

Sept 20th 2017

Over the years we have had many excellent speakers and some really interesting evenings, but our September session was exceptional. Angela Dodd-Crompton came to give us a talk on a lost garden near Newton Abbot, and held us all spellbound from beginning to end. She has spent 12 years researching the history of the Italian Garden at Great Ambrook, a private house and estate in a secluded valley near Ipplepen. The Italian garden had become completely overgrown and lost to sight during the middle of the twentieth century.

She first explained how a large wooded area near the house had been bought in 1988 by a couple living on the estate who feared a clay pigeon shoot near their home. They slowly started to cut through the brambles and undergrowth to find the hard landscaping beneath. Gradually more and more of the garden was cleared and more features emerged. Angela and her husband heard of the lost garden through their local horticultural society, and were shown it in 2005 by the owner, by then in his eighties. She was so intrigued that she began to research the facts about the man who commissioned the garden, Arthur Smith Graham, who lived at Great Ambrook at the turn of the last century until his death. Over the years she has done more than twelve thousand hours of work and found out a fascinating story, and is clearly passionate about the place. Her enthusiasm was palpable.

Angela took us on a photographic tour of the garden showing the various structures in their present state. As we progressed around and she explained the lay out and showed the pictures, we were all absorbed in the excitement of the discoverers and what they had found. In many areas she has been able to find ‘before and after’ photographs, which were fascinating to compare. The garden had been built between 1909 and 1912 on a scale that was perfect for entertaining large parties. It had been beautifully designed and planted out professionally from the best nurseries. Angela has followed up all the leads she could find, and after describing the plan of the garden, went on to tell us how she found out about the gardeners who worked there. She had worked on discovering the designer, and the builder, and was able to tell us about them and their careers. This work spanned many personal interviews, discovering old photographs held by various families, census returns, books of reference and all types of institutions and sources.

This painstaking and thorough amount of work has enabled Angela to get the garden listed by Historic England. This is a very difficult thing to achieve, and has entailed even more work. However, it has hopefully saved the garden for the future. In 1988 it escaped the guns, and recently escaped being sold for house building. The new owners plan to set up a restoration programme and Angela has offered to try to organise a tour of the garden, which is otherwise private, in 2018.

The story told was enthralling and like the best kind of detective story, albeit with no murders! Angela is now writing a book on the Italian Garden and I imagine everyone who was at the meeting will want to read it. I certainly will. Circumstances meant that Angela and her husband had driven straight to the Parish Hall from Gatwick after a visit to Italy, so it was even more impressive that she gave such an amazing presentation.

Isobel Hepworth

July 19th 2017

An intriguing set of circumstances brought Tony Sheffield from Australia to Newton St Cyres, this summer. He contacted the History Group for information and as a result agreed to give a talk in the Club Room on July 19th, to which all were welcome. Helped by his partner Kate, he had put together his first ever PowerPoint talk, to tell us all about his house in Moss Vale, New South Wales, which was built in 1917 by Helena Wyatt, of East Holme.

Jean Wilkins opened the evening by fixing us firmly in the late nineteenth century when Helena Florence Wyatt (1878 – 1948) was growing up in the village. This was when the mining industry was closing down and when the new school was opened. It is also when farming became difficult as grain was imported from Canada. Old Clay Hill Lane was still there and she would have walked up and down it. She was 10 when 16 year old Annie Sansom was murdered in 1888, and would have known of her. She was in her twenties when the old squire died in 1901. Mary Long has researched the Wyatt family and Tony Sheffield read out the detailed story of her parents and grandparents which Mary has given him. Originally a cooper, Thomas Wyatt settled here in the 1820s then became publican of the Old Inn in the centre of the village. His eldest son and Helena’s father, William, farmed at West Holme and then took over East Holme as well, and after his death in 1903 her brother Harold took over the farms, with Helena as his housekeeper. In 1912, Harold married and later moved away (after 1916). In the meantime, Helena took a third class passage on the White Star Liner ‘Ceramic’ to Australia.

Quite why she did this, what contacts she had, and what money, is all unknown. However, she went up to the Southern Highlands, south of Sydney, and in 1915 bought 20 acres of land on the Throsby estate at the cost of £30 an acre, and by 1917 had a house built. Dr Charles Throsby was a surgeon from Leicester who had gone out to Australia in 1802 and worked for the colony. He was granted 1000 acres of fertile land in Moss Vale, which his nephew, also Charles, inherited. Charles Junior married and built a house and stables, all now Heritage Listed. Part of the estate was divided into residential lots in 1911 and it was this land that Helena bought. She took out a private mortgage in 1916 with Frances Throsby, because women could not, at that time, hold a bank mortgage. Tony had a photograph of Helena in the garden of friend’s house in Moss Vale, standing with another friend, a well- known lady racing driver. In 1926 Helena sold the house, called ‘Charnwood’, to Dorothy Crace, a well-connected and wealthy Australian woman, who moved in the same circle. Thanks to the internet, Tony had been contacted by a lady from Yorkshire whose relation, Florence, had been the live-in cook for Miss Crace in 1930, and she had ‘Charnwood’ recipes she was able to give him. This really adds a personal touch to the story of the house. Miss Crace also had the gardens professionally planted out and they are now mature and notable.

Helena Wyatt stayed in the area, living in Elizabeth Street, but also went back to England more than once. She died in a nursing home in Hove in 1948. There is no record of her working in Australia, but she may have been a private tutor, as she was listed as a schoolteacher on her original passage out.

The house Helena built was owned by Dorothy Crace until her death in 1959, and then changed hands several times over the next 40 years. The original plot of 2½ acres was subdivided and the house name changed to ‘Cherry Lea’. On one of the half acres of mature gardens sold off, Tony’s partner, Kate, who came from Moss Vale, had a 1920s house brought from Sydney. The procedure, not uncommon in Australia, is to remove the roof, cut the house in half, move it, and then reconnect it on the new site! This house is now called ‘Charnwood’ in memory of the original house next door. Tony bought ‘Cherry Lea’ in 2009 and has restored it, added a photographic studio totally in keeping with the original building, and painstakingly researched the house history, because a building a century old is notable in Australia.

Tony was born in England, in Windsor, and is a professional photographer. After living in many places around the world, he has settled in the Southern Highlands, and he made clear what a beautiful area it is. He showed us a short film of the region, and this reinforced the decision made by Helena Wyatt to live in an area with a fertile soil, a temperate climate with all four seasons, plenty of rainfall and lovely mountains, valleys and woods. Many parts of Australia are not so naturally blessed.

Tony has done an impressive amount of research, following up all the leads he can, and is still actively finding out more about the people whose stories link to the house in Moss Vale. We heard a fascinating tale and went away wondering about the still unanswered questions.

Many thanks go to Tony from the History Group and all those at his talk, for such an interesting evening. Thanks also go to Mary Long for sharing her research into the Wyatt family.

Isobel Hepworth

An intriguing set of circumstances brought Tony Sheffield from Australia to Newton St Cyres, this summer. He contacted the History Group for information and as a result agreed to give a talk in the Club Room on July 19th, to which all were welcome. Helped by his partner Kate, he had put together his first ever PowerPoint talk, to tell us all about his house in Moss Vale, New South Wales, which was built in 1917 by Helena Wyatt, of East Holme.

Jean Wilkins opened the evening by fixing us firmly in the late nineteenth century when Helena Florence Wyatt (1878 – 1948) was growing up in the village. This was when the mining industry was closing down and when the new school was opened. It is also when farming became difficult as grain was imported from Canada. Old Clay Hill Lane was still there and she would have walked up and down it. She was 10 when 16 year old Annie Sansom was murdered in 1888, and would have known of her. She was in her twenties when the old squire died in 1901. Mary Long has researched the Wyatt family and Tony Sheffield read out the detailed story of her parents and grandparents which Mary has given him. Originally a cooper, Thomas Wyatt settled here in the 1820s then became publican of the Old Inn in the centre of the village. His eldest son and Helena’s father, William, farmed at West Holme and then took over East Holme as well, and after his death in 1903 her brother Harold took over the farms, with Helena as his housekeeper. In 1912, Harold married and later moved away (after 1916). In the meantime, Helena took a third class passage on the White Star Liner ‘Ceramic’ to Australia.

Quite why she did this, what contacts she had, and what money, is all unknown. However, she went up to the Southern Highlands, south of Sydney, and in 1915 bought 20 acres of land on the Throsby estate at the cost of £30 an acre, and by 1917 had a house built. Dr Charles Throsby was a surgeon from Leicester who had gone out to Australia in 1802 and worked for the colony. He was granted 1000 acres of fertile land in Moss Vale, which his nephew, also Charles, inherited. Charles Junior married and built a house and stables, all now Heritage Listed. Part of the estate was divided into residential lots in 1911 and it was this land that Helena bought. She took out a private mortgage in 1916 with Frances Throsby, because women could not, at that time, hold a bank mortgage. Tony had a photograph of Helena in the garden of friend’s house in Moss Vale, standing with another friend, a well- known lady racing driver. In 1926 Helena sold the house, called ‘Charnwood’, to Dorothy Crace, a well-connected and wealthy Australian woman, who moved in the same circle. Thanks to the internet, Tony had been contacted by a lady from Yorkshire whose relation, Florence, had been the live-in cook for Miss Crace in 1930, and she had ‘Charnwood’ recipes she was able to give him. This really adds a personal touch to the story of the house. Miss Crace also had the gardens professionally planted out and they are now mature and notable.

Helena Wyatt stayed in the area, living in Elizabeth Street, but also went back to England more than once. She died in a nursing home in Hove in 1948. There is no record of her working in Australia, but she may have been a private tutor, as she was listed as a schoolteacher on her original passage out.

The house Helena built was owned by Dorothy Crace until her death in 1959, and then changed hands several times over the next 40 years. The original plot of 2½ acres was subdivided and the house name changed to ‘Cherry Lea’. On one of the half acres of mature gardens sold off, Tony’s partner, Kate, who came from Moss Vale, had a 1920s house brought from Sydney. The procedure, not uncommon in Australia, is to remove the roof, cut the house in half, move it, and then reconnect it on the new site! This house is now called ‘Charnwood’ in memory of the original house next door. Tony bought ‘Cherry Lea’ in 2009 and has restored it, added a photographic studio totally in keeping with the original building, and painstakingly researched the house history, because a building a century old is notable in Australia.

Tony was born in England, in Windsor, and is a professional photographer. After living in many places around the world, he has settled in the Southern Highlands, and he made clear what a beautiful area it is. He showed us a short film of the region, and this reinforced the decision made by Helena Wyatt to live in an area with a fertile soil, a temperate climate with all four seasons, plenty of rainfall and lovely mountains, valleys and woods. Many parts of Australia are not so naturally blessed.

Tony has done an impressive amount of research, following up all the leads he can, and is still actively finding out more about the people whose stories link to the house in Moss Vale. We heard a fascinating tale and went away wondering about the still unanswered questions.

Many thanks go to Tony from the History Group and all those at his talk, for such an interesting evening. Thanks also go to Mary Long for sharing her research into the Wyatt family.

Isobel Hepworth

25th April 2017

On Tuesday 25th April the History Group hosted a visit from the Chulmleigh History Society. They wanted to come to Newton St Cyres and find the village behind the A377, which of course is what they usually see as they travel through en route to other places.

Fifteen visitors assembled in the village car park at 10 o’clock that morning and four of us – Jean Wilkins, Roger Wilkins, Brian Please and Isobel Hepworth - were waiting to welcome them. After the important business of a cup of tea or coffee with cake and biscuits, everyone settled down to a short power point presentation from Jean, which showed old photographs of the village. She explained how the road layout changed in the nineteenth century and how other lanes and houses have existed in the past. Using a big map of the Parish, Jean explained how Newton St Cyres was really a collection of hamlets, each with its nucleus of old listed houses. She also explained how each had been important at different times, Norton for seasoning the wood for the Cathedral, Half Moon for milling and East Town (Sand Down Lane) for mining. She also illustrated the road widening after the fire at the Crown and Sceptre in 1962, and this interested Chulmleigh very much.

Next the group divided into two for an hour’s tour. Jean and Roger took one group towards the ford and Old Beams, Zoe and Derek Rhydderch Evans having very kindly agreed to show them around their beautiful 14/15th century home. It was originally built as a hall with high walls and a central fire whose smoke escaped through louvres in the roof. Chimneys and floors were added later. For many years it was the Agricultural Inn until it lost its licence in 1909. Amongst the Chulmleigh party was John Mair, whose relative, Alfred Abrahams, lived in the Agricultural Inn until he was 13 years old, when he was orphaned and went to live with John’s family. Alfred wrote a charming book about his life in Newton in the early 20th century. The group then walked down towards West Town, with Jean pointing out the many old cottages, some of which were originally small farmhouses. Eastholme and Halses were picked out as more old hall houses. Looking up the hill, the mining areas could be pointed out before the group returned.

The other group walked up through the churchyard, with Brian and Isobel. Brian led a tour around the churchyard, pointing out the Wayside Cross, some of the gravestones, the way across to Newton House and the arboretum entrance. Once inside the church he went through a brief history of the main features and then Isobel talked about the Quicke Hatchments, after which Brian finished off by describing the Royal Arms of James II and some of the intriguing bosses carved in the roof timbers, which he is in the process of researching.

The groups then met outside the Hall and swapped over so that they each had done both tours. We finished at 12.30 so that Chulmleigh could proceed to Cakeadoodledoo and then on to Downes House for their afternoon visit there.

Our summer outing, on the afternoon of Saturday 10th July, was a return visit to Chulmleigh to be shown around this historic town. Many of the nineteen of us enjoyed a buffet lunch at the local golf club, before everyone met outside The Red Lion pub in the centre of Chulmleigh. We walked down to the church of St Mary Magdalene where Roy Gosney gave us a detailed explanation of the architecture. It is certainly an impressive building, rising 450’ above sea level, near Little Dart and the Taw rivers. It was originally a collegiate church, rather than a parish church, with a rector and prebends whose duty was to say prayers for the dead. Although there was almost certainly a Saxon church on the site, the present building dates from the 15th century and is built in the perpendicular style. There is a late 15th century font, but the most impressive feature is a wonderful late medieval rood screen, intricately carved and painted, which somehow survived the Reformation. The wagon roof has its bosses beautifully painted, so that they stand out clearly, and its curved timbers ending with carved and painted angels, their wings picked out in gold.

The town of Chulmleigh grew wealthy from the medieval wool trade, and so has many old and interesting buildings. The main road north to Barnstaple used to run through the town, with steep access up from the valleys, and so because the town is on a hill, it was by passed when the toll road was built, and it became cut off from the main traffic. We walked from the church into the centre of the town, where five roads meet. On the way we passed the original Girls’ School, which became the Rectory, and the Town Hall and Market, its old arches now blocked in to make rooms. Chulmleigh has, like many Devon towns, suffered serious fires, and we were shown a charred door from the last of these in the 19th century. The King’s Arms, in the centre of town, was an inn until the 1820s but it is now a house, and this is true of many of the other buildings, such as the old smithy, the old dairy, and the old boys school. However, the Congregational Church, now shared with the Methodists, is still a place of worship. It has the old pulpit from the Anglican church, memorials to the families of the town who have worshipped there, a lovely old working clock and is an old and interesting building. We walked past the Old Court House Pub, which did indeed house the magistrates’ court at one time, and also had a gibbet outside. Opposite was its Maltings House, now a residence, and we finished down the road at the Old Bakehouse, where we were given a very pleasant tea with biscuits and cakes, and were able to discuss our afternoon and thank our hosts for their hospitality.

Isobel Hepworth

15th March 2017

We went far back in time for our evening on 15th March, to the first inhabitants of Devon in the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age, 10,000 years ago. This was the starting point for Bill Horner’s talk on the importance of the Lower Exe, Culm and Creedy Valleys in the Prehistoric and Roman periods. Bill Horner is the County Archaeologist and last came to speak to us in 2011when he gave a general talk on Devon’s various sites from prehistory to the Second World War, based on aerial photographs. It was clear that he had plenty more that he could tell us. This time he concentrated on the area to the north and west of Exeter, where our village is situated, and explained that the geography of the surrounding hills and valleys makes this fertile place a nodal point in the landscape. The land is productive, all routes westwards and eastwards funnel through it, and even in prehistoric times the rivers and estuary were navigated. The influential landscape historian, WG Hoskins, called it ‘the vestibule of the West Country’.

The Mesolithic era is dated roughly between 8,000 and 4,500 BC, when the first hunter gatherers entered the area as the ice retreated. They would have moved up the river valleys and made clearings in the thick woods, to attract the animals they would hunt for food. During the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, which followed, more land was cleared for farming, settlements and enclosures were established and trading contacts made. The landscape holds the evidence of these times, in flint scatters of arrowheads and tools which can be found by field walking, as Christopher Southcott has shown on Lake Ridge. The flint would be traded and Beer was one source. Stone axes might come from as far away as the Lake District or the Lizard, and Hembury ware bowls and pots were produced all over the area from the local clays.

Bill showed us aerial photos which showed the various types of settlement marks left in the landscape from this period. He began with the causewayed enclosures at Raddon and Nymet Rowland. There are others in Devon, and it is thought that these earthworks were used for feasting and trading, and possibly funerary rites, rather than being permanent settlements. May be they were defensive, but it seems that warfare then was more complex and that there were ritualised forms of conflict. Long barrows were used over time for communal burial of the dead, and we saw a photo of a possible one at North Tawton. Henges (post or stone circles with a bank and ditch) existed all over Britain, the most famous being Stonehenge, but in Devon the best preserved sites are on Dartmoor, where the use of stone and lack of farming preserved many sites from the Neolithic and Bronze Age. However, there is one at Bow, where the marks left by a post and timber circle remain.

The Bronze Age is dated from c. 2,500 to c. 750 BC when the use of iron became more widespread. Round barrows date from this time, often in groups, and often high on the skyline to indicate the ancestors’ presence and the ownership of land. Ploughing has reduced many of these mounds so that they only show as crop marks, but there is a concentration here at Upton Pyne and along towards Bow. Photos of ring ditches at Hayne Barton, and a huge enclosure at Rewe, are further evidence of the amount of activity in this area. Field systems too show in the soil as excavations are carried out ahead of roadworks e.g.at Feniton, though they show most clearly in the reeves on Dartmoor. These and other settlement enclosures reveal the small farming communities who lived here and one of these enclosures shows from the air at the top of Tin Pit Lane. There would have been a wooden enclosure around a farm house and outbuildings. During the Iron Age, hill forts were built, the nearest to us being Cadbury Castle, though there are others such as Milber Down near Newton Abbot.

The enclosure at the top of Sandown Lane, with a double ditch, was a farm dating from the middle of the Iron Age, around 200 BC and was used into the Romano-British period to about the second century AD. It was interesting to see the recent excavation photographs.

The Roman invasion brought a period of more intense occupation and land use. The Romans were keen to exploit the mineral wealth of the south west, and iron, silver and tin from the local mines was funnelled through the Exeter area. Of course as this was a military zone at first, this area was well garrisoned and controlled from the large fortress they built at Exeter and the fort at Topsham, the main port on the Exe at the time. There was also a large fort at Tiverton (Bolham) to secure the routes eastwards. There was smaller garrison at Bury Barton Farm, Lapford, which again shows as crop marks, an enclosure at Ide, and a probable Signal Station on Stoke Hill, which would have passed on alerts by fire or by trumpet along a network of similar stations. There were questions about the whereabouts of the Roman military road going west from Exeter through Coleford, North Tawton and Okehampton. Parts of its route are known, but the section joining these to Exeter has not been found, and there is no proof that it did go along the ridge south of the village, as many of us suspect!

The Roman civilian period lasted for nearly four centuries, and there are some traces of the farms and settlements here, such as the enclosure in Sandown Lane, already mentioned, a tile found in Silverton, and a turnspit found in Rewe. More significant is a Roman Villa at Downs House outside Crediton. This is a substantial building and may well indicate that the road ran close by.

It was clear, by the end of Bill Horner’s talk, that this area has been a busy place for many centuries, since the first hunter gatherers came into the landscape. It was very interesting to see the evidence of the inhabitants over such a long time span. Our thanks go to Bill Horner for the wealth of information he presented so clearly.

Isobel Hepworth

18th Jan 2017

Force and Sons have been in business in Exeter for over 220 years, and although latterly they have been most well known as estate agents, they were involved in other areas of operation in the past. David Force and his brother Stephen run the business at the moment, and David came to talk to us on Wednesday 18th January for our first meeting of 2017. He lives and works in Dawlish, although he grew up and was educated in Exeter. His interests have led him to involvement in the town and its museum, and he is now finishing his book on the history and buildings of Dawlish.

He explained how estate agency evolved over the years. Its beginnings were in the 18th century when home ownership was rare. Large landowners had houses and estates and they needed managers to run the daily business of looking after their affairs. When properties changed hands they needed an auctioneer to handle the sale. As time progressed and wealth grew, smaller house and landowners such as wealthy business people, also needed an estate manager and the services of an auctioneer. Eventually the growth of individual property ownership meant that house agency for the general public developed.

There are several family firms in the Exeter area such Helmores, Whitton and Laing and Fulfords, but Force are the oldest established ones still in family ownership. The firm was started in 1790 by John Force, who came from a family of traders in Dawlish. He set up premises in Cathedral Yard as an auctioneer, and David showed us an original poster from 1825 advertising the sale by John Force at auction of a Freehold Brewery with its attendant pubs and premises. Interestingly, Force and Sons sold the same premises again in the late 1980s although by then it had changed usage. John Force worked in a Georgian city very different from the present Exeter. The population was around 20,000 and the town was compact and surrounded by villages such as Whipton and Pinhoe, which are now part of the city. The economy was still strongly agricultural and sanitation and water supplies were primitive even though Exeter was the sixth largest town in England. John had fourteen children, including three sets of twins, but they did not all survive to adulthood. His seventh child, Charles, joined the business and set up as a house agent in 1820 from premises in Sidwell Street, just outside the city wall.

Soon after, in 1825, Charles started to diversify into undertaking, building and shop fitting, sanitation and electrical engineering. These areas of the business were pursued for the next 150 years until the 1960s, when the undertakers was the final department to be closed and the firm concentrated on estate agency and auctioneering, which David still does. Over time the city grew in size and population, and stagecoach transport gave way to railways. This of course made business much easier, as a property agent could then move around more easily, without having to go on horseback or stage. The horse tramway in Exeter was introduced in 1882, but the last one ran in 1905 when electric ones took over and David described how William Sidney Force, a Mason, Father of the Council and Justice of the Peace, had opposed this change.

In 1970, the lovely late Queen Anne building in Sidwell Street, which had been the Force offices since 1820, were due for demolition for the rebuilding which was planned for the area. Billy Force, David’s uncle, who had run the shop fitting department, died in the 1990s and it was then that he and his brother went into their uncle’s shed to deal with the seven or eight large boxes and trunks of records which they knew were stored there. The archive proved to be a very useful and valuable record of the city. For instance, Victorian house particulars were so detailed that they showed all the gardens, greenhouses and even flower beds, very helpful to a lady who was researching Victorian gardens. Much of the material was given to the County Archive, but David kept sale posters, letters, photos and business cards and leaflets, which we were able to look at during and after the meeting.

The First World War inevitably caused a general downturn in business, as the men marched away, transactions slowed down and money was scarce. This and the depression that followed threatened the future of the firm, but by this time the new generation was going off to train and gain experience in London and elsewhere. David’s grandfather came back from London and through the sale of a hotel in Bournemouth, where ‘Uncle Billy’ had been working, was able to make enough profit to put the business back on its feet and continue. The Second World War again was hard, but Force’s range of activities made for resilience and the rebuilding afterwards brought work and enabled businesses to thrive again.

David himself began to work for the family firm during his school holidays at the age of 7 or 8, stuffing envelopes with particulars. During his working life, the pace has changed from one where coffee with the local bank manager, lunch at home, and tea and chat have given way to a very commercial and cut throat world. Once people in similar local businesses would meet in the pub on a Friday night to discuss the week, but now things are too competitive for this.

David is an experienced and relaxed speaker, well able to entertain and educate at the same time. He gave his talk with plenty of photographs and interesting historic material, which was passed around, such as business cards and auction posters. His reminiscences and the stories about his family and forbears were informative, interesting and amusing. During questions he commented on how the internet has changed the nature of the business, and yet to be really effective, personal skill and knowledge are still necessary, and hopefully the following generations of Forces will adapt and survive as their ancestors have done so successfully. We would like to thank David for such an interesting evening.

Isobel Hepworth

Nov 16th 2016

A packed audience in the Parish Hall Club Room on 16 Nov heard Michael Winter give a fascinating talk on ‘Farming in Devon in the 20th Century’. Michael is Professor of Land Economy and Society at Exeter University and also has plenty of practical experience on his own small farm.

He traced the development of farms and farming taking many examples from Exbourne, where he had carried out detailed studies. Exbourne, like Newton St Cyres, has a combination of some free-draining redland and some heavy clay culm soils. Both parishes were, over the century, predominantly grassland, used by cows, beef cattle and sheep, but with some cereals.

Changes in farms and farming in Exbourne were relatively slow from the 1800s through to around 1950, with the number of farms falling slowly from around 40 in 1833 to 34 in 1951 Likewise the number of employed farm workers (excluding the farmer and family labour) declined slowly from a peak of 55 in the 1850s to 40 in 1921 and 34 in 1951. There were bigger changes in the second half of the century, as outlined below. A characteristic of the farms throughout early part of the century was that they were mixed - the biggest area was in grass, but there were also small areas of cereals (mainly barley and oats, often grown as a mixture in ‘dredge corn’) and potatoes and a range of livestock including a few cows, sheep, pigs, poultry and work horses. The area of cereals in the parish was highest around 1880 at 700 acres, falling gradually to only 250 acres by 1931. Even during the World Wars the area increased only to around 450 acres. Livestock numbers showed relatively little variation, with the total number of cows being between 70 and 110, with individual farms generally having only 3 to 10, and around 500 sheep. There were 60 to 80 farm horses until around 1930 and then a rapid decline.

The rate of change both in Exbourne, as in the country as a whole, became much faster towards the middle of the 20th Century. Michael explained the effects of WW2 and the subsequent technological revolution. He described the County War Agricultural Executive Committees and their work. These Committees were appointed by central government, but headed by leading local farmers who had the respect of others in the farming community.. They had draconian powers and could impose supervision orders and, in extreme circumstances, evict farmers. They were responsible for the planning and control of farming and dictated aspects of cropping and stocking, principally to achieve the policy of increasing the production of cereals and potatoes required to feed the Nation.

In order to help with this work a detailed study of all farms was carried out. This assessed both land characteristics and the performance of the farmers, with farms being assessed in categories A (good) to C. There were some pithy comments on the report forms. The comments on two low-rated farms were ‘old age and lack of labour’ and another ‘Personal failings. Tenant is a woman and is unable to do any better’. I don’t think the latter comment would now be politically acceptable! Both of these farms were put under supervision.

Michael indicated that although wartime farming made a big contribution to increasing food production, there were no major technological changes or increases in yield per acre or per animal at that time and only small structural changes in farming.

All this was to change in the post-war technological revolution. A combination of government policy to support farming, high prices and the application of new science to farming led to massive changes both in output and in farm structure. Wheat yields had remained around 30 bushels per acre from the mid 19th Century to around 1950, but then showed a massive increase to 85 bushels by 1980 [a bushel is a volume measure and for wheat is equivalent to about 63 lbs]. Improved varieties, better cultivation, increased fertiliser use and the development of agrochemicals for controlling weeds and diseases all contributed to improvement in yields. It was a similar picture with milk yields per cow - after having been fairly static these nearly doubled in the 30 years from 1950, with better feeding and disease control, animal breeding and substitution of Shorthorns with Friesians all playing a part.

Mechanisation, with more and bigger tractors, combine harvesters, forage harvesters and balers, led to the elimination of farm horses by 1960 and, together with milking machines, resulted in massive reduction in employed farm workers, with the number in Exbourne falling from 34 in 1951 to just 3 full time and 1 casual worker in 1980. The number of farms in Exbourne fell from 34 in 1951 to 21 in 1980, with progressive increase in owner occupation, so that by 1980 only about 250 acres were tenanted compared with some 1400 acres tenanted early in the century.

Another important change was increased specialisation and the decline of mixed farming. Michael illustrated this with information from Exbourne and from 41 parishes near Holsworthy, an area with conditions much more suited to grassland than to cropping. In those parishes the area of crops (as opposed to grass) fell from 23% to 14% between 1954 and 1979, whilst the numbers of sheep and cattle nearly doubled.

Michael has extended the Exbourne study to look at changes to the 26 holdings with over 5 acres in 1941. Of these, 16 have ceased to exist as independent farms and only one is a conventional commercial farm providing full time work for a farmer and members of his family. It was pointed out that the number of separate farms in Newton St Cyres has also greatly reduced over this period, but the major change has been the Quicke Estate becoming farmed ‘in house’ rather than having a large number of tenant farms.

The talk was followed by plenty of questions, comments and recollections. Norman Wheadon recalled ploys used by farmers to mislead the War Ag inspectors. The inspectors checked the areas sown to crops like potatoes to see whether farmers were fulfilling their quota, but Norman recalled that farmers might leave the middle part of a field unplanted, hoping that the inspectors would only see the outside of the field and assume all was in potatoes! But generally farmers in Devon made a full contribution to increasing production in times of need in response to national policies. The 20th Century certainly saw a revolution in farms and farming methods.

17th December 2016

Our Christmas meeting always aims to be a social evening, as well as having an historical theme. This time, on Wednesday 17th December, we had an enjoyable time singing carols, enjoying a buffet with mince pies and wine, and listening to Christopher Lee’s well-chosen selection of readings.

The evening began with the carols, led by Sonja and Colin Andrews from Morchard, who have a folk singing background, and an interest in traditional and early carols. They were both strong singers as well as instrumentalists, and had us joining in straight away. Sonja sang ‘The Boar’s Head Carol’ herself ; it was first written down in Oxford in 1521, and celebrates the ancient tradition of feasting on a boar’s head, and has a Latin chorus. The tune is simple but the words evocative of the Middle Ages.

We then all joined in with ‘While Shepherds Watched’. This is such a well-known carol, but Sonja and Colin told us how in the past local parishes often had different versions of the same basic carol, with different tunes being used. Following a lead from a reference at the British Library, researchers in Morchard parish looked in the parish chest where, amongst many other records, two old alternative tunes were found for this carol, one of which we sang with Sonja teaching us the lines.